Last year for Halloween, I wrote the blog, The Night Witches (click here to read the blog). It was then I decided to try and write an annual Halloween blog. So, this year I’d like to introduce you to the “Ghost Army,” a group of talented artists whose job it was to deceive and hide things from the enemy.

Prior to D-Day on 6 June 1944, Gen. Patton commanded the fictitious First United States Army Group (FUSAG). The FUSAG was created to convince the Germans that Patton was preparing for a cross-channel invasion at Pas de Calais. As part of the ruse, Patton commanded a group made up with dummy equipment. (Maybe that was his punishment for slapping a soldier or two.) However, known as “Operation Quicksilver,” Patton’s FUSAG was part of the larger deception scheme named “Operation Fortitude.” Along with the British network of double agents, FUSAG accomplished its mission and likely saved the lives of thousands of Allied soldiers (click here to read the blog, The Double Cross System).

Our blog today focuses on another secret group whose responsibilities were to deceive the Germans. However, most of their activities occurred after the invasion of Normandy. The unit and its mission were so secret the men were instructed to stay silent about their war time activities for fifty years and all files pertaining to the “Ghost Army” remained classified until 1986.

Did You Know?

Did you know that the 1960s animated prime-time sitcom, “The Jetsons,” was set in 2062⏤one hundred years from its television debut? (The cartoon show had its debut on 23 September 1962.) Looking back on the show, it is amazing how much future technology was first highlighted on this futuristic television show.

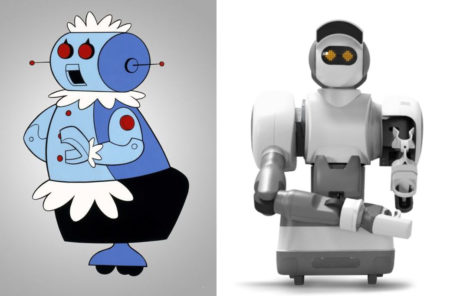

Despite running for only one season, the show’s writers eerily predicted technological items that we take for granted sixty years later. How about video conference calls? (Mr. Spacely liked to chew out George Jetson.) Moving sidewalks, flying drones and flat-screen television sets were introduced (including Zoom). Robots included Uniblab, the “smart” robot intended to replace factory workers, Rosie the robotic maid, and we certainly can’t forget ‘Lectronimo, the pet dog robot (poor Astro must have considered looking for a new human). I think today you can find each of these robots on Amazon. Flying cars were a popular mode of transportation in 2062. Although we haven’t come that far yet, I’m sure Jeff Bezos and Elon Musk are working on it.

Another interesting fact is that “The Jetsons” was the first prime-time network series to be broadcast in color.

The 23rd Headquarters Special Troops

Throughout the history of the world, deception has always been used to mislead enemy forces or civilians (e.g., the Greek Trojan Horse). Even Gen. George Washington used deception tactics against British forces during the Revolutionary War. However, it wasn’t until World War II that America first formed a military unit specifically to train, equip, and put soldiers on the battlefield to deceive the enemy. (British success in deceiving the Germans resulting in the victory of the Battle of El Alamein in October 1942 left an indelible impression on American military command.) This new unit was called the 23rd Headquarters Special Troops with the nickname, “Ghost Army.”

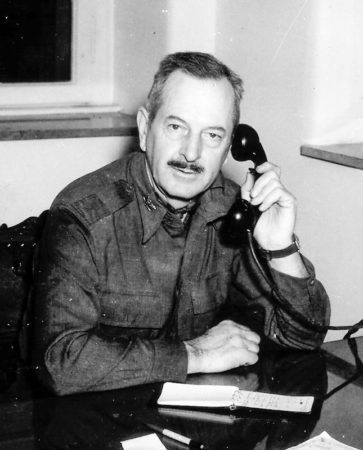

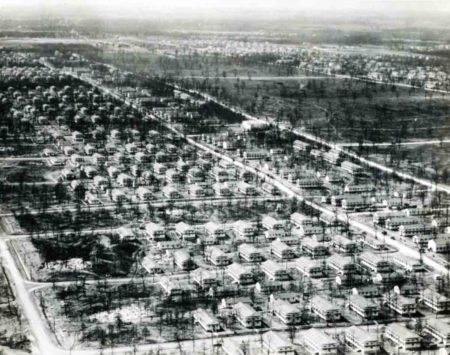

The unit was activated in January 1944 at Camp Forrest, Tennessee. Col. Harry L. Reeder (1891−1947) was chosen to command the top-secret Ghost Army, the first mobile, multimedia, tactical deception unit. It was authorized for eighty-two officers and 1,023 soldiers. The men selected were artists, engineers, and professional soldiers and some of its famous members included the fashion designer, Bill Blass (1922−2002), painter Ellsworth Kelly (1923−2015), and photographer Art Kane (1925−1995). The average I.Q. of the Ghost Army was 119 and among the highest of any military group (i.e., above average, or “bright”). I guess I’ll have to look up the average I.Q. for the men and women at Bletchley Park for comparison purposes.

Three existing battle units and one newly created unit made up the 23rd. The largest unit was the 603rd Engineer Camouflage Battalion. The 379 men were responsible for visual deception including the creation of inflatable rubber tanks, jeeps/trucks, and artillery. Signal Company was a group of 296 men who carried out radio deception. They called it “spoof radio.” Phony traffic nets were created whereby the men impersonated radio operators from real army units. They continued to mimic the real operator long after he had moved on to a new location. The 3132nd Signal Service Company was staffed with 145 men, and it was the sonic deception unit. Their job was to mount speakers on trucks and go around the front lines mimicking army units moving around at night. The fourth group was the 406th Combat Engineers. These men were fighting soldiers and they provided perimeter security for the rest of the Ghost Army. They would frequently use their bulldozers to simulate tank tracks as part of the visual deception.

The Ghost Army was able to simulate two entire divisions, or about 30,000 “imaginary” men and their equipment. Using phony convoys, phantom divisions, and make-believe headquarters, the enemy was fooled about the strength and locations of actual army units. During the last year of the war, the Ghost Army participated in twenty-two major deceptions in Europe from Normandy to the Rhine.

Selected Operations

The 23rd arrived piecemeal in France in late June and early July 1944. They set up shop near Sainte-Mère-Église, the town captured by the 82nd Airborne Division on the morning of D-Day. The men immediately began to develop their first “division” by inflating the dummy tanks and artillery pieces. According to Beyer and Sayles, several Frenchmen on bicycles unexpectedly came upon the 603rd and saw the men lifting “40-ton tanks.” They couldn’t believe what they were seeing.

As the 23rd began its operations, Col. Reeder sent the instructions to his line commanders to downplay the MILITARY aspect and emphasize SHOWMANSHIP. Senior officers saw the 23rd as a traveling road show rather than a conventional fighting unit. Their mission was to present itself to the Germans as the 2nd Armored Division, the 9th Infantry Division, and the Seventh Corps depending on the situation. Convincing the enemy required proper scenery, costumes, principals, extras, dialogue, and sound effects. Some of the men even went into the towns and villages and acted like they were colonels and generals. They spread fake information so that collaborators and German spies would be fooled.

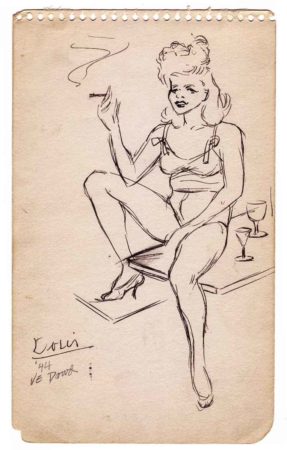

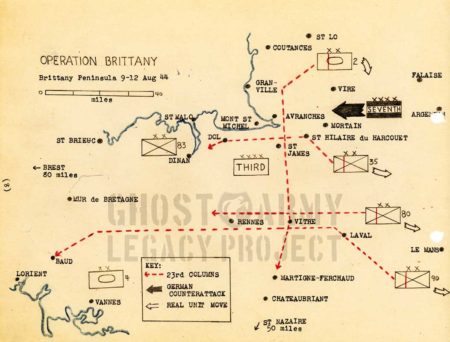

Operation Brittany in July 1944 was all about tricking the Germans into thinking Gen. Patton’s tanks were headed in a completely different direction. This successful deception was one of the reasons why Gen. Patton was able to race across France. Following Operation Brittany, the men of the 23rd participated in the celebrations of the liberation of Paris. In-between parties, some of the artists were able to create artwork of the city and the Parisians.

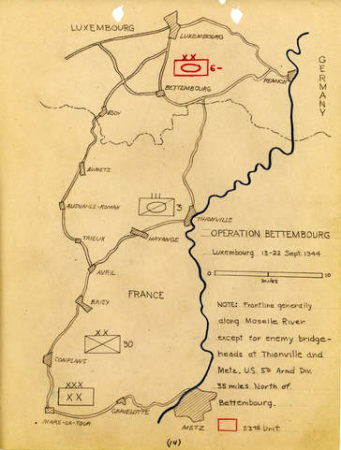

Operation Bettembourg in September 1944 saw Gen. Patton’s tanks stopped near Metz because of a lack of fuel. (Patton’s pace was so fast that he often outran his supply lines.) The general was worried the Germans would counterattack a weak or thin spot in his line. The 23rd came to the rescue by creating the impression there was greater strength in the “gap.” More than two dozen rubber tanks were set up along with tank noises from loudspeakers. After four days, the Germans decided not to attack and eventually left.

Operation Kodak during the Battle of the Bulge was all about drawing the Germans’ attention away from the effort to relieve Bastogne. In mid-December 1944, the 23rd was masquerading as the 75th Infantry Division at Bastogne. When the Germans broke into their sector, the 23rd had to withdraw quickly or they would have been annihilated. Nearby soldiers were angry when they suddenly found the 75th was nowhere to be found (thus confirming the deception success). Gen. Bradley ordered Patton to rush to the area while from the rear, the 23rd came up with a plan to convince the Germans that Patton’s 4th and 80th Infantry Divisions were being put into reserve when in fact, just the opposite was true.

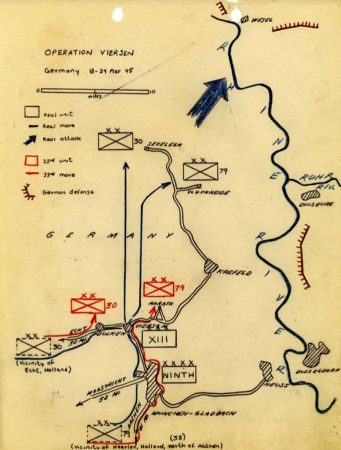

Operation Viersen was the final mission for the 23rd and it took place on 24 March 1945 near the Rhine River. The plan was to deceive the Germans into thinking that two Ninth Army divisions (about 30,000 men) were about to cross the Rhine at Krefeld, a point ten miles south of where the actual crossing was to take place. They used fake radio traffic, hundreds of rubber vehicles, dummy antiaircraft guns, and a fake airfield with fake aircraft. Sounds of moving trucks and equipment were broadcast by loudspeakers mounted on moving vehicles. Sounds of building pontoon bridges were duplicated and broadcast across the river to the Germans. When it came time for the real crossing, the only German resistance came from a very limited number of troops who were completely confused.

Only Nine Remain

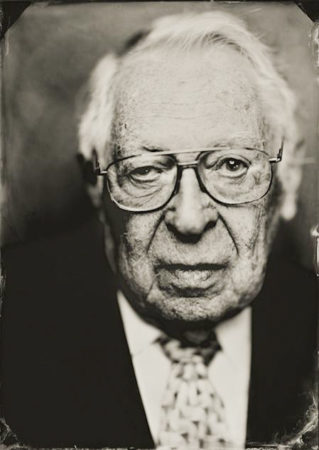

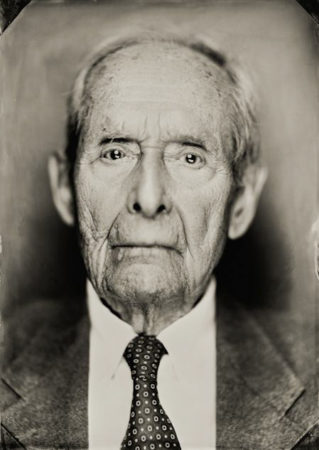

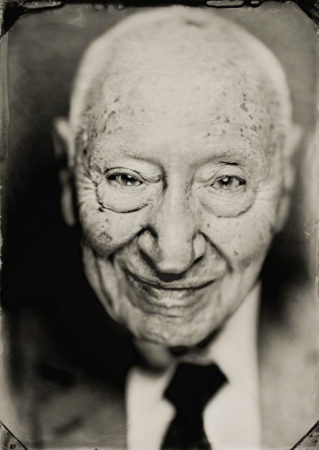

Today, there are only nine surviving members of the Ghost Army and I will introduce you to four former soldiers. Of the four I have highlighted, only Seymour Nussenbaum is still alive.

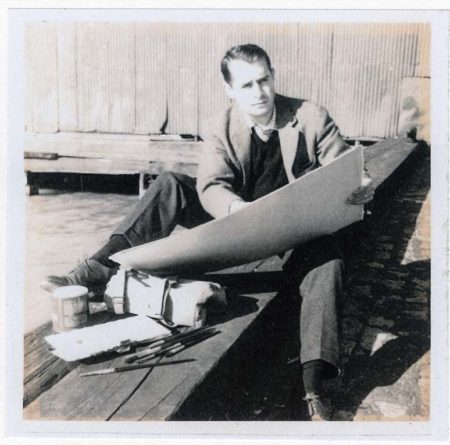

John Jarvie (1922−2017) studied art in New York City before enlisting on 27 October 1942. He requested and was assigned to the 603rd Engineer Camouflage Battalion. Jarvie was a jeep driver and one of the most talented artists in the unit. John recalled, “We were sleeping in hedgerows and foxholes, but nothing kept us from going someplace to do a watercolor.” After his discharge, Jarvie began his long career in art. John Jarvie passed away in 2017 and is buried in Arlington Cemetery in his hometown of Kearny, New Jersey.

Seymour Nussenbaum (b. 1923) was born in Romania before his parents immigrated to the United States where they settled in New York City. He attended school at the Fiorello LaGuardia High School of Music and Art and Performing Arts. Seymour enlisted in February 1943 and was assigned to the Ghost Army where he was part of the team that made counterfeit patches as well as other tasks such as inflating the dummy equipment. After his discharge, when asked what he did during the war, Seymour answered, “I blew up tanks⏤which wasn’t a lie!” Seymour’s wife, Vera, escaped from Germany on the first Kindertransport, three weeks after Kristallnacht. (click here to read the blog, Kinderstransport and Mr. Winton) Seymour Nussenbaum is one of the nine surviving Ghost Army veterans.

Arthur Shilstone (1922−2020) received his art training at Pratt Institute (as did Seymour Nussenbaum) and enlisted on 19 November 1942. Assigned to the Ghost Army and specifically, the 603rd, Shilstone created many paintings, sketches, and illustrations of his experiences. His most famous painting was of two astonished Frenchmen watching four soldiers pick up one of the dummy tanks. Shilstone said, “They looked at me, and they were looking for answers, and I finally said: ‘The Americans are very strong.’” Shilstone had a long and prolific career as an illustrator, including twelve-years with Life Magazine. He was one of eight “official” NASA artists, and his work hangs in many well-known locations including the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

Nicholas Leo (1922−2022) was born to Italian immigrants who settled in New York. Nick enlisted in November 1942 and was assigned to the Ghost Army’s Signal Company Special. He was one of the few Ghost Army soldiers who landed in Normandy on D-Day. Nick met his future wife, Pierrette, while stationed in France (the witnesses at their wedding were former German POWs). His service days were not over as Nick joined the Naval Reserve after World War II and served as a radio man on a naval vessel during the Korean conflict. His professional career was divided into three categories: as a musician (Nick was an accomplished accordion player), an artist, and architect. He was married to Pierrette for seventy-four years (she passed away in 2020).

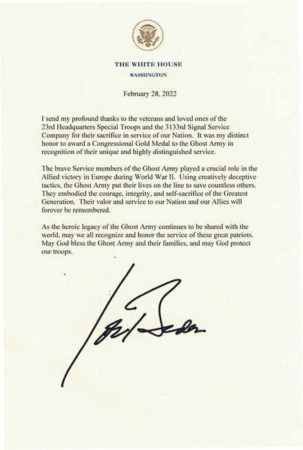

Congressional Gold Medal

On 1 February 2022, President Biden signed “The Ghost Army Congressional Gold Medal Act” into law.

“The United States is eternally grateful to the soldiers of the 23d Headquarters Special Troops and the 3133d Signal Service Company for their proficient use of innovative tactics during World War II, which saved lives and made significant contributions to the defeat of the Axis powers.”

– Text of the Ghost Army Congressional Gold Medal Act.

The official history of the Ghost Army was written by Capt. Fred Fox (1917−1981) in 1946. It remained classified until 1996. Neither Col. Reeder nor Capt. Fox lived long enough to talk about their war time experiences in the Ghost Army. Every member was sworn to fifty years of secrecy.

Next Blog: “We Will Meet Again”

Correspondence and Commentary Policy

We welcome everyone to contact us either directly or through the individual blogs. Sandy and I review every piece of correspondence before it is approved to be published on the blog site. Our policy is to accept and publish comments that do not project hate, political, religious stances, or an attempt to solicit business (yeah, believe it or not, we do get that kind of stuff). Like many bloggers, we receive quite a bit of what is considered “Spam.” Those e-mails are immediately rejected without discussion.

Our blogs are written to inform our readers about history. We want to ensure discussions are kept within the boundary of historical facts and context without personal bias or prejudice.

We average about one e-mail every two days from our readers. We appreciate all communication because in many cases, it has led to friendships around the world.

★ Learn More About The Ghost Army ★

Beyer, Rick and Elizabeth Sayles. The Ghost Army of World War II: How One Top-Secret Unit Deceived the Enemy with Inflatable Tanks, Sound Effects, and Other Audacious Fakery. New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2015.

Fox, Donald Hardie. Capt. Fred Fox of the Ghost Army & France: a story for the 75th anniversary of D-Day. Fox Head Press, 2019.

Fox, Capt. Fred. The Official History of the 23rd Headquarters Special Troops. Published by the U.S. Government, 1945 and declassified in 1996. The document is held by the National Archives, College Park, Maryland. The official transcript can be found on the Ghost Army Legacy Project website: click here.

Kneece, Jack M. Ghost Army of World War II. Gretna, LA: Pelican Publishing Company, 2001.

Souter, Gerry. The Ghost Army: Conning the Third Reich. London: Arcturus Publishing Limited, 2019.

Ghost Army Legacy Project. Click here to visit the website.

The Ghost Army: World War II’s Artists of Deception. Click here to visit the website.

Disclaimer:

There may be a chance that after we publish this particular blog, the video links associated with the blog are no longer accessible. We have no control over this. Many times, whoever posts the video has done so without the consent of the video’s owner. In some cases, it is likely that the content is deemed unsuitable by YouTube. We apologize if you have tried to access the link and you don’t get the expected results. Same goes for internet links.

What’s New With Sandy and Stew?

Sandy and I are on the ms Rotterdam right now. We should be about halfway across the Atlantic on our way to New York City by the time you read this. While the cruise is billed as “The 150th Anniversary Transatlantic Voyage of the Rotterdam,” it’s really a repositioning cruise. The ship is going to Fort Lauderdale in time for the Caribbean cruising season.

We have taken quite a bit of research material with us. There are a lot of sea days, and on prior cruises, we were very productive using that time. Our goal is to finish the second volume in the Nazi Occupation series. Once we return home, I only need to finish off the introduction section and we will be ready to hand the rough manuscript over to Carol, our editor. I’ll keep you posted.

Thank you to all of you who subscribe to our bi-weekly blogs. It seems there isn’t a day that goes by where we don’t increase our readership. Please let your history buff friends and family members know about our blog site and blogs.

Someone Is Commenting On Our Blogs

It was good to hear from John W.M. again. John’s new book is scheduled to be published shortly and several months ago, I had the honor of reading a draft of the manuscript. I enjoyed the book and look forward to making it a part of my permanent library. In the meantime, John pointed out some new facts about the RAF and in particular, one of the reasons why the Spitfires beat up on Luftwaffe aircraft. I will add this information to our recent blog, Biggin Hill, for the benefit of future readers (click here to read the blog).

John has agreed to write a guest blog for us. The working title is The Five Things I Learned in Writing “The Hunt for the Peggy C.” We will publish his guest post in December. Stay tuned.

If there is a topic you’d like to see a blog written about, please don’t hesitate to contact me. I love hearing from you so keep those comments coming.

Share This:

Follow Stew:

Find Stew’s books on Amazon and Apple Books.

Please note that we do not and will not take compensation from individuals or companies mentioned or promoted in the blogs.

Walks Through History

Walks Through History

Copyright © 2022 Stew Ross